Description:

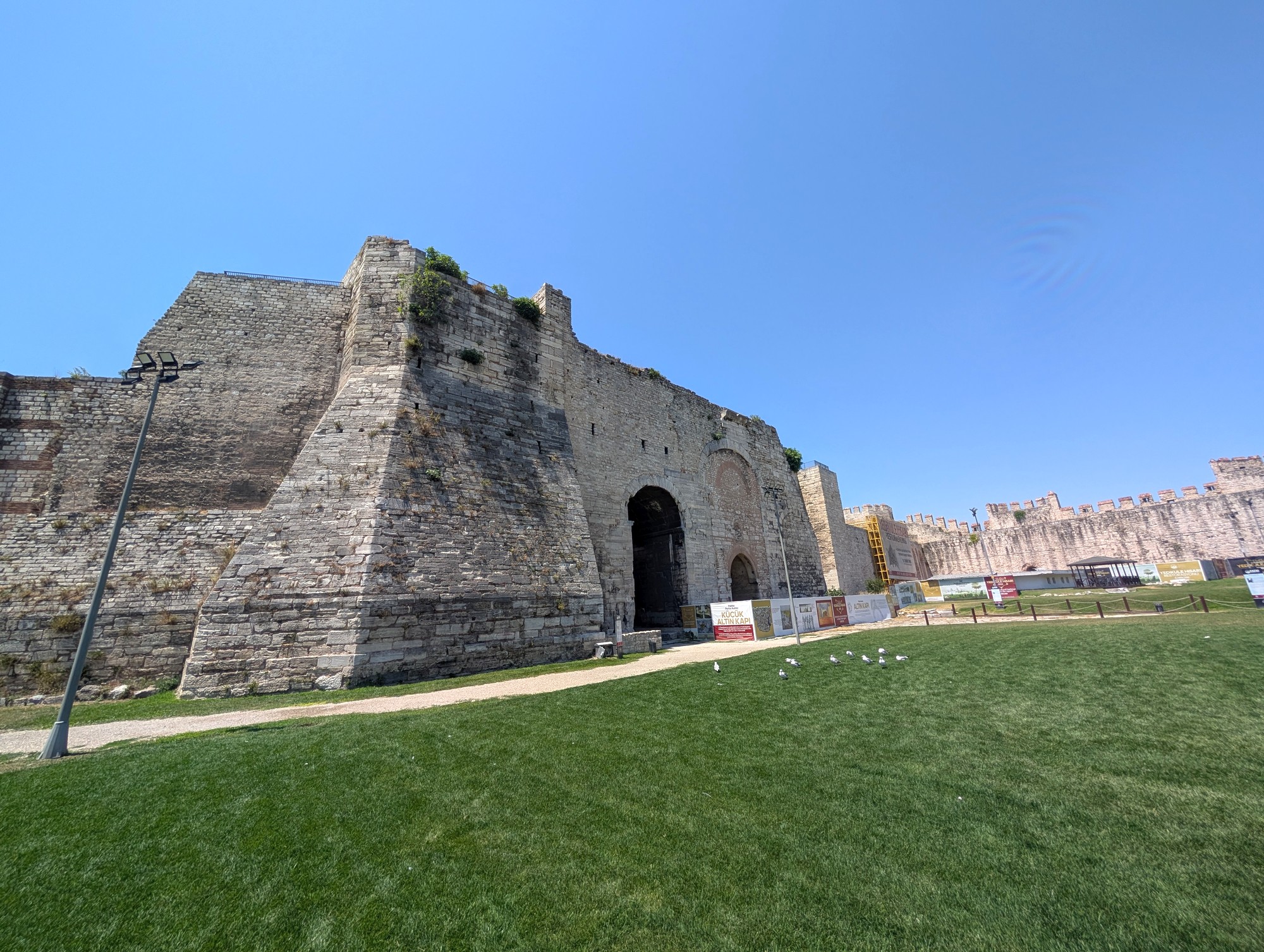

Rising where empires once met and clashed, the Yedikule Fortress — the Fortress of the Seven Towers — has long stood as one of Istanbul's most imposing landmarks. Built in 1458 by Sultan Mehmed II, the conqueror of Constantinople, it fused the grandeur of Rome with the ambition of the Ottomans, enclosing the mighty Golden Gate of the Theodosian Walls within its new ring of towers. More than just a fortress, Yedikule became infamous as a royal dungeon, a place where ambassadors, nobles, and rebels awaited their fate. Over the centuries, its looming walls gave birth to tales of intrigue, escape, and execution, ensuring its place in both legend and memory.

History of fortifications

The idea of fortifying this spot was far from new. As early as the 5th century, a circular stronghold may have stood here, remembered in later sources as the Castrum Rotundum — though both its layout and exact position remain a mystery. Centuries later, another fortress rose behind the Golden Gate of the Theodosian Walls. First begun under Emperor John I Tzimiskes (969–976) and completed during the reign of Manuel I Komnenos, it was armed with five towers and became known as the Pentapyrgion, the Fortress of Five Towers. This imposing citadel, however, met a violent end in 1204, when the armies of the Fourth Crusade stormed Constantinople and left much of the city in ruins.

Then, after years of civil war, Byzantine Emperor John V Palaiologos (1341–1391) sought to secure his position by building a fortress at the Golden Gate of the Theodosian Walls of Constantinople, known as the Kastellion tes Chryseias. Short on materials, he dismantled three nearby churches — the Church of All Saints, the Church of Forty Martyrs, and what remained of the Basilica of St. Mokios — and used their stones to raise his walls. The new stronghold formed a ring of towers and ramparts that joined the mighty Theodosian Walls to the west and the sea walls to the south. Though the exact layout of this fortress has been lost to time, by 1390 the emperor had taken up residence there. His triumph was short-lived: the following year Sultan Bayezid I forced him to demolish the fortress, threatening to blind his son Manuel, whom he held captive.

Nearly half a century later, John VIII Palaiologos tried to rebuild it, but Sultan Murad II quickly put a stop to the effort. Only after the city itself had fallen to the Ottomans did the idea come to life again. In the years following his conquest of Constantinople, Sultan Mehmed II turned his attention to monumental building projects that would cement his rule and reshape the city. Among his earliest works were the first imperial palace, the Saray-i Atik, and the Yedikule Fortress. Thus, in 1457–1458, Mehmed the Conqueror raised a new fortress on the same spot, echoing John V's vision but on a grander scale, adding three massive new towers, located on the inner side of the Theodosian Walls to the four ancient ones. The result was the formidable Yedikule, the Fortress of the Seven Towers, that still looms today.

Yedikule was conceived as the Ottoman Empire's official treasury. Contemporary visitors described it as one of the Sultan's palaces, and with good reason: each tower guarded a different store of imperial wealth — from documents and arms to coins, silver, and gold ingots. Protecting the treasury was considered a matter of state survival, a lesson drawn from Ottoman tradition, and Yedikule was built as much for defence as for storage. Only in the sixteenth century was the treasury moved inside Topkapı Palace, after which the fortress gained a darker role as the prison of high-ranking captives. Among others, ambassadors from states at war with the empire were usually imprisoned here.

Strategically positioned on the shores of the Sea of Marmara, Yedikule incorporated the monumental Golden Gate of the Byzantine Theodosian Walls into its design. Two of the gate's towers and two Byzantine-era towers to their north and south were preserved and reused, while Mehmed added three massive new towers to form a near-pentagonal plan. A central axis ran from the Golden Gate to the Ottoman tower opposite, dividing the complex into two symmetrical halves. At the very heart of the courtyard stood a small domed building, the Conqueror’s Mosque, marking both the midpoint of the fortress and the symbolic presence of its founder.

Within the walls of Yedikule, life once bustled in a way that might surprise modern visitors. The fortress’s vast inner courtyard was not just a military space but a small community of its own: it housed the garrison’s residences, creating what was essentially a self-contained city block behind the looming towers. This settlement endured for centuries until the 19th century, when the old houses were cleared away and, in their place, a girls’ school rose up — a striking change of purpose that reflected the shifting priorities of the Ottoman state.

In 1838, the fortress’s outer gate was reopened, breathing new life into the monumental complex. Not long after, the mighty towers that had once terrified prisoners and awed visitors found themselves serving a far more practical function — they became gunpowder magazines, storing the empire’s ammunition within their thick stone walls. By the close of the century, however, the fortress was reborn once more. In 1895, it was officially converted into a museum, its grim dungeons and solemn towers reframed as sites of history rather than instruments of power.

The transformation did not stop there. In more recent decades, the great courtyard has taken on an entirely new role as a stage for the living arts. An open-air theatre was installed, and today the fortress echoes not with the clang of chains or the crack of gunfire, but with music, theatre, and cultural festivals that draw both locals and visitors. In this way, Yedikule continues to reinvent itself — from imperial treasury to prison, from arsenal to museum, and now, to a gathering place for celebration and memory beneath the watch of its seven towers.

Seven Towers of Yedikule Fortress

Clockwise, starting from the Ruined Tower 8 of Theodosian Walls at the southwestern point of the fortress, there are the following seven towers that gave Yedikule its name:

1. Ruined Tower

This tower, in Turkish referred to as Yıkık Kule, was the 8th tower of the Theodosian Land Walls of Constantinople, which no longer exists. Its exact form, appearance, and details such as height and architectural features are not well documented in surviving architecture. The loss of Tower 8 is not unusual: many of the towers along the Theodosian Walls have been damaged or destroyed over the centuries due to earthquakes, repair work, reuse of materials, urban encroachment, or neglect.

The tower stood at the southwestern point of Yedikule. The fortress of Yedikule includes a section of the Theodosian Walls between towers 8 and 11 and the area between Tower 8 and Tower 11 defines the western border of the Yedikule ensemble.

2. Southern Marble Tower

It is the south tower of the Golden Gate (Porta Aurea) in the Theodosian Walls, technically being the 9th one counting from the south. In Turkish, it is sometimes called Güney Mermer Kule, meaning simply the South Marble Tower. However, there exists another, much more evocative name for this structure - Genç Osman Kulesi - Turkish for Young Osman Tower.

The reason this tower was named after Young Osman, one of the youngest sultans in Ottoman history, is that the place where the sultan was murdered is on the second floor of this tower. Osman II, who reigned between 1618 and 1622, was still a teenager when he came to the throne. After his failed campaign against Poland at the Battle of Khotyn in 1621, he blamed the Janissaries, the elite but increasingly unruly corps of the Ottoman army, for their lack of discipline and effectiveness. He began planning drastic reforms, including abolishing the Janissary corps altogether and replacing them with a new army raised from Anatolia and possibly even from Arab provinces. His contempt for the Janissaries and his outspoken plans sealed his fate.

In May 1622, rumours of Osman's plans spread. The Janissaries, furious at the threat to their privileged position, mutinied in Istanbul. They stormed the imperial palace, overthrew Osman II, and installed his uncle, Mustafa I, on the throne. Osman was seized, stripped of power, and humiliated — an unprecedented act in Ottoman history, since deposing a young sultan was already a shock, but keeping him alive posed a dangerous political risk.

Osman II was taken to the grim dungeons of Yedikule Fortress (Yedikule Zindanları), infamous as a prison for high-ranking captives. He was only 18 years old at the time. Witnesses describe how he was beaten, insulted, and left in despair, begging for mercy and even for food and water. Then, on 20 May 1622, Janissaries entered his cell and strangled him with a bowstring — the traditional Ottoman method of execution, as spilling royal blood was forbidden. According to chroniclers, Osman resisted fiercely, showing the strength and spirit of youth, but was overwhelmed and killed in the dungeon.

The murder of Osman II shocked his contemporaries. A reigning sultan had never before been so brutally deposed and executed by his own soldiers. His death at Yedikule became a symbol of Janissary corruption and unchecked power, and later sultans remembered it as a warning. Eventually, in 1826, the Janissaries themselves were annihilated during the so-called Auspicious Incident — a grim echo of Osman's unrealized plans.

3. Northern Marble Tower

The northern tower of the Golden Gate (Porta Aurea) in the Theodosian Walls is known in Turkish as the Kuzey Mermer Kule meaning North Marble Tower. This imposing structure, built largely of gleaming white marble, formed one half of the monumental triumphal archway erected by Emperors Theodosius I and Theodosius II to celebrate military victories. Numbered as the 10th tower when counting from the south along the line of the land walls, it stood opposite its twin, the South Marble Tower, together framing the most prestigious entrance to Constantinople.

In the late Byzantine period, the area around the Golden Gate took on added significance when Emperor John V Palaiologos built a fortress enclosing the gate and its towers in the 14th century. Later, when Sultan Mehmed II rebuilt the complex as Yedikule Fortress after 1458, the Northern Marble Tower became incorporated into the Ottoman fortification. It thus shifted from a triumphal landmark into a functional part of the city's defensive and prison architecture.

Architecturally, the Northern Marble Tower is massive and solidly built, with a square base and thick walls that could withstand both time and attack. It was one of the strongest points along the wall, commanding both the landward approach and the adjoining curtain walls.

4. Ahmed III Tower

This is the last of the Byzantine-era towers of the Theodosian Walls incorporated into Yedikule Fortress, standing in the north-west corner of the fortress, to the north of Porta Aurea. This Tower number 11 is much better known as the Tower of Ahmet III, named after the sultan who rebuilt it after the earthquake. In its Byzantine form, the tower is said to have had a square plan, but it was rebuilt as an octagonal form in the years 1724-1725. The tower was also known as Pastorama Kulesi, but the source of this name and its meaning remain unclear.

During the reign of Sultan Ahmed III, i.e. from 1703 to 1730, Istanbul was struck by the Great Earthquake of 1719, one of the most destructive disasters of the early 18th century. The tremor devastated large sections of the city, toppling houses, mosques, and stretches of the ancient Theodosian Walls. According to chroniclers, the Yedikule Fortress was also damaged, and the tower later known as the Ahmed III Tower suffered partial collapse. Its upper sections crumbled, forcing repairs during the Tulip Era. Those reinforcements gave the tower its association with Ahmed III, whose name it carries to this day.

The Ahmed III Tower at Yedikule owes its name to one of the most unusual sultans of Ottoman history. Built originally as a part of Byzantine fortifications, the tower took on renewed significance during the reign of Ahmed III, a ruler remembered for the elegance and refinement of the Tulip Era (Lâle Devri). Ahmed III presided over a time when the empire, exhausted by wars, briefly turned its gaze inward toward art, poetry, gardens, and architecture. It was in his reign that the Topkapı Palace Library was founded, tulips became a symbol of imperial taste, and fountains, kiosks, and pavilions blossomed across Istanbul. Even the famed Fountain of Ahmed III in front of Hagia Sophia, with its delicate ornamentation and poetic inscriptions, reflects the sultan's love of beauty.

Yet, this era of refinement stood in sharp contrast to the grim reputation of Yedikule. The tower that later bore Ahmed's name may have been repaired or refitted in his reign, but instead of tulips and fountains, it guarded dungeons and echoing halls where prisoners scratched their laments into stone. Some foreign envoys and rebellious pashas who passed through Yedikule in this period left behind accounts of fear and deprivation.

Thus, the Ahmed III Tower embodies a striking paradox: linked by name to a sultan who ushered in a golden age of Ottoman art and leisure, but itself a silent witness to the darker duties of the state. It reminds visitors that Ottoman history was never only about splendour or only about cruelty — but often about both, standing side by side, much like Ahmed III's ornate fountain in the city centre and the forbidding towers of Yedikule on its edge. The inscription "Maşâallahu ta'ala" (With the permission of Almighty God) on a marble plaque on the tower's exterior facing the street reflects the tower's dual character: an expression of divine sanction and imperial authority, yet also a reminder of the fragility of human power in the face of revolt and earthquake.

5. Treasury Tower

At the north-eastern corner of Yedikule Fortress rises the Treasury Tower (Hazine Kulesi), its name a direct reflection of its prestigious function in the Ottoman era. Sometimes referred to as the Northern Tower (Kuzey Kule), it once safeguarded the empire's most precious possessions within its thick stone walls.

Although Yedikule was originally constructed as an inner citadel by Sultan Mehmed II after his conquest of Constantinople, it soon assumed an additional role as the imperial treasury. Before the treasures were relocated to Topkapı Palace during the reign of Sultan Murad III (1574–1595), the Treasury Tower was the empire's stronghold of wealth and memory.

Guarded day and night by around 250 soldiers, the tower housed a remarkable array of valuables: gilded weapons and armour, ornate coats of arms, rare antiquities, and priceless state documents. Perhaps most impressively, it also stored the spoils of conquest brought back by Sultan Selim I (1512–1520) — known as Yavuz Sultan Selim (the Grim or the Resolute). His victories in Egypt, Syria, and Iran yielded treasures of both material and symbolic weight, including artefacts tied to the Caliphate and the guardianship of Islam's holy cities, Mecca and Medina.

Selim's campaigns not only filled the vaults of Yedikule with riches but also transformed the Ottoman Empire itself. With his assumption of the caliphal mantle, the empire shifted its cultural and political centre of gravity from the Balkans toward the heartlands of the Islamic world, cementing its status as the leading Muslim power of the 16th century.

Like its companion towers — the Cannon Tower and the Tower of Inscriptions — the Treasury Tower was originally topped with a striking two-tiered pointed cone roof, which gave the fortress a distinctive skyline visible from land and sea. Although the roof has not survived, the massive tower still whispers of the immense wealth and power once guarded within its walls.

6. Tower of Inscriptions

Known today as the Kitabeli Kule in Turkish, this circular tower has carried many names through the centuries: the Dungeon Tower, the Prison Tower, and, owing to its position directly across from the famed Porta Aurea (Golden Gate) of Constantinople's Theodosian Walls, the East Tower (Doğu Kulesi). It is the easternmost of the seven towers that give the fortress of Yedikule its name. The tower was added after the Ottoman conquest of Constantinople in 1453, when Sultan Mehmed II reshaped the Byzantine structure into a fortified complex symbolizing the new imperial order.

Despite its seemingly neutral name, the tower's history is anything but gentle. For much of the Ottoman period, it served as a grim prison for foreign envoys, dignitaries, and even ambassadors — men who had travelled long distances to reach the imperial capital, only to find themselves locked in its cells during times of political tension. According to Ottoman practice, Christian and foreign captives were often confined here, while Muslim prisoners were usually held in the nearby Golden Gate’s marble towers.

Many detainees left behind haunting traces of their captivity: on either side of the tower's gate, one can still find inscriptions and carvings etched into the stone. These graffiti, in languages ranging from Latin to Hungarian, form a unique archive of despair and resilience, and earned the tower its enduring association as the Tower of Inscriptions.

The tower's interior has not withstood the centuries unscathed. The wooden mezzanine floors, once used by guards and prisoners alike, have long since vanished, and the conical roof that once crowned the structure collapsed over time. What remains is a stark shell — its massive walls and weathered carvings bearing silent witness to centuries of imperial power, diplomatic intrigue, and human suffering.

7. Cannon Tower

The tower erected on the circular plan at the southern end of the Yedikule Fortress is one of three monumental Ottoman towers commissioned by Sultan Mehmed the Conqueror, following his dramatic capture of Constantinople in 1453. This round tower stood not only as part of the fortress’ defensive system, but also as a symbol of the new Ottoman order established upon the ancient Byzantine walls. Over the centuries, the tower acquired several evocative names: the Supply Tower, the Maiden’s Tower, and the Millet Tower, reflecting the different functions and stories attached to it. Yet, it is the name Cannon Tower that most clearly conveys its purpose within Mehmed's military vision.

What sets the Cannon Tower apart from its Ottoman-period companions — the Treasury Tower and the Tower of Inscriptions — is its ingenious internal design. Instead of stairs, its floors are linked by a ramp, a rare feature in Ottoman military architecture. Historians suggest that this ramp allowed heavy cannons to be rolled upward for deployment. The broad openings visible on the terrace level would then have served as embrasures for positioning these formidable weapons, turning the tower into a true artillery platform.

Contemporary engravings and travellers’ sketches reveal that the tower was once crowned with a distinctive two-tiered pyramidal roof, adding both elegance and height to its silhouette. Though this roof has not survived the centuries, the massive walls and architectural ingenuity of the Cannon Tower still echo the ambition of Mehmed II, the young sultan who reshaped the course of world history.

Notable prisoners of Yedikule Fortress

Yedikule Fortress, often remembered today as a museum and landmark, was also one of the most dreaded prisons of the Ottoman Empire. For high officials who had fallen out of favour, especially grand viziers, its dungeons frequently marked the final stop before execution. Because of its symbolic weight as both a fortress and treasury, sources frequently associate it with political purges. Still, it is important to distinguish carefully between cases that are well-documented and those where later tradition or local lore may have embellished events.

Some executions are firmly established in reliable historical accounts. Mahmud Pasha Angelović, who served twice as grand vizier under Mehmed II, was dismissed and executed in 1474 after imprisonment in Yedikule. His fate is widely recorded in both Ottoman chronicles and modern scholarship. Similarly, Tabanıyassı Mehmed Pasha, a powerful vizier under Murad IV, was confined in Yedikule and put to death in 1637 after suspicions of disloyalty. Another grand vizier, Deli Hüseyin Pasha, briefly held office in 1659 before being imprisoned and executed at the fortress. These three cases are generally accepted as certain examples of viziers executed at Yedikule.

Other names surface in the historical record but with less certainty about the precise location of their death. Çandarlı Halil Pasha, executed after the conquest of Constantinople in 1453, is often said to have been imprisoned and beheaded in Yedikule. While many reputable sources repeat this, including official cultural heritage sites in Istanbul, the details are less securely documented than for the later cases. Likewise, Kara Davud Pasha, notorious for his role in the killing of Sultan Osman II, whose sad story has been described in the section devoted to the Southern Marble Tower, was executed after losing power himself. Some accounts place his imprisonment at Yedikule, but strong evidence that his actual execution occurred inside the fortress is lacking.

Moreover, the sultans' political opponents from abroad were held in the fortress, including ambassadors from powers at war with the Ottoman Empire. Some of them, such as Napoleon's emissary François Pouqueville who was imprisoned there from 1799 to 1801, felt quite at ease at Yedikule, devoting themselves to literary work and maintaining constant correspondence with their government. On occasions, he convinced his guards to let him travel through Constantinople and along the Bosphorus all the way to the Black Sea. His time at Yedikule inspired extensive descriptions in his celebrated work "Voyage en Morée, à Constantinople, en Albanie, et dans plusieurs autres parties de l'Empire Othoman, pendant les années 1798, 1799, 1800 et 1801", where he portrayed the fortress not merely as a prison but as a vantage point from which to study Ottoman life and politics.

For others, however, Yedikule was a place of final reckoning. Among the most poignant cases was that of David Komnenos, the last emperor of Trebizond. After the fall of his Black Sea stronghold to Mehmed II in 1461, David and his family were initially treated with honour. But suspicion soon grew that he was plotting with foreign allies, and in 1463, he was confined within Yedikule. There, he and several members of his household were executed, extinguishing the last flicker of Byzantine imperial legitimacy. His death was later remembered by Orthodox tradition as a martyrdom, and centuries later his remains were solemnly reinterred in Trebizond.

Another prominent inmate in Yedikule was István Maylád, a Hungarian nobleman of the Majláth family. He rose to prominence during the mid-16th century as voivode of Transylvania, at a time when the region was torn between Habsburg and Ottoman influence. After the death of King John Zápolya in 1540, Transylvania became a buffer zone where loyalties shifted rapidly, and magnates like Maylád sought to preserve their authority by balancing the demands of both Vienna and Istanbul. His position, however, was precarious, as suspicion of betrayal or double-dealing could quickly bring ruin. Maylád eventually fell out of favour with the Ottoman authorities, who suspected him of leaning toward the Habsburg side in the ongoing contest for control of Hungary. Arrested and transported to Constantinople, he was confined in the notorious Yedikule fortress. There he languished in harsh conditions, cut off from allies and stripped of his former rank, before dying in custody in 1550.

The person who died in the same year in Yedikule was Bálint Török, one of the most powerful Hungarian magnates of the early 16th century, rising to prominence during the reign of King Louis II. He held vast estates and in 1527 was appointed ban of Belgrade, commanding a critical frontier stronghold in the struggle against the Ottomans. Like many nobles of his time, Török sought to manoeuvre between the rival claims of the Habsburg king Ferdinand I and the Ottoman-backed John Zápolya, attempting to secure both his influence and his lands in the fractured kingdom. His prominence, however, made him both an indispensable ally and a dangerous rival, and the shifting alliances of the age soon left him exposed. The Ottomans eventually grew suspicious of his loyalties, particularly his connections with the Habsburg court, and in 1541 they lured him into a trap. Invited to negotiations, Török was seized and taken to Constantinople, where he was imprisoned in the Yedikule fortress. There Török remained in harsh captivity for nearly a decade, stripped of his titles and estates, until his death in 1550. His end, like that of István Maylád, reveals how the great lords of Hungary and Transylvania could swiftly fall from privilege to ruin when caught between the two empires that contested their homeland.

Among Yedikule's prisoners were some of the most remarkable Poles of the 17th century, caught in the tangled diplomacy and power struggles of their era. The first of them was Samuel Korecki, a daring Polish nobleman and seasoned military adventurer. During the ill-fated Battle of Cecora in 1620, Korecki was captured by Ottoman forces, his boldness, and reputation marking him as a valuable and dangerous prisoner. He was transported to Yedikule Fortress. Within its cold stone walls, Korecki experienced the harsh realities that awaited high-ranking captives: isolation from allies, constant uncertainty about his fate, and the stripping away of his noble privileges. Efforts were made to secure his release. Polish envoys, including the famed diplomat Krzysztof Zbaraski, pleaded on his behalf, but the negotiations faltered. After nearly two years of captivity, in 1622, Samuel Korecki was executed — likely by strangulation, the method reserved for high-profile prisoners in Yedikule. His body was secretly smuggled back to Poland and interred in Korets, preserving his memory among his countrymen.

The second of the Poles imprisoned in Yedikule in the 17th century was Samuel Twardowski, although his was a less gruesome fate. He was an envoy of King Władysław IV Vasa who arrived in Constantinople in 1622–1623 to navigate the delicate negotiations between the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth and the Ottoman court. Despite his official status and careful diplomacy, he was seized and confined within the fortress's forbidding walls, where suspicion often outweighed merit. Though the precise length of his imprisonment remains unclear, the ordeal left a lasting mark. Eventually released, Twardowski returned home, carrying with him the experience of captivity and the vivid impressions of a court where a single misstep could spell ruin. His writings, including a poetic diary of the mission, preserve a unique window into the world of 17th-century diplomacy and the precarious life of an envoy in a foreign empire.

The fortress was also the site of one of the most harrowing episodes in Romanian memory. Constantin Brâncoveanu, prince of Wallachia, had ruled for more than a quarter of a century, carefully navigating the shifting alliances between Ottoman Istanbul, Habsburg Vienna, and the rising power of Moscow. Yet, his wealth and diplomacy aroused suspicion, and in 1714 Sultan Ahmed III ordered his arrest. Dragged to Yedikule with his family, Brâncoveanu was tortured and pressed to abandon his Christian faith. On 15 August, he and his four young sons were led to execution; steadfast in their refusal to convert, they were beheaded together within the fortress walls. Canonized by the Romanian Orthodox Church in 1992, Brâncoveanu remains a symbol of both princely dignity and religious martyrdom.

Count Pyotr Andreyevich Tolstoy, a prominent Russian statesman and diplomat, found himself ensnared in the intricate web of 18th-century European politics. In November 1701, he was appointed as Russia's first regularly accredited ambassador to the Ottoman Empire. His mission was fraught with challenges, as he navigated the delicate balance between the Russian and Ottoman empires. Tensions escalated when Swedish King Charles XII sought refuge in Ottoman territory after his defeat at the Battle of Poltava in 1709. Tolstoy's demand for Charles XII's extradition was perceived as a diplomatic affront, leading to his imprisonment in the Yedikule Fortress in October 1710. Tolstoy's incarceration there was a significant diplomatic incident, straining Russo-Ottoman relations. He remained imprisoned until April 1712, when a truce was concluded between the two empires. Upon his release, Tolstoy returned to Russia, where he resumed his diplomatic duties and continued to serve the Russian state with distinction.

From grand viziers and regional magnates to foreign envoys and princes, Yedikule Fortress was a stage on which the high-stakes drama of empire, loyalty, and survival played out. Its walls, both protective and punishing, bore witness to ambition, intrigue, and, for many, the finality of judgment.

Ghost Stories and Legends of Yedikule Fortress

One of the most chilling tales of Yedikule Fortress tells of a pagan prisoner condemned to die in the dungeons. As his life slipped away, he whispered a curse in a strange, ancient tongue that resembled Latin. He vowed that the souls of all who suffered in Yedikule would remain trapped within its walls until the return of Christ. Even now, when night falls and the wind sweeps through the fortress, some claim they can hear faint wails or hushed voices echoing from the dungeon towers, as if the walls themselves remember the anguish of centuries past.

Deep within the Inscriptions Tower lies the infamous "Bloody Well," a place shrouded in dark legend. Executions were said to take place above its yawning depths, and at the very bottom, a hidden tunnel supposedly opens to the Sea of Marmara. Some stories whisper that the heads of prisoners were sent tumbling into the sea through this secret passage. Visitors often pause at the well's edge, imagining the echoes of despair that might still rise from its shadowed depths, carried by the cold, damp air.

The fortress seems almost alive with the memories of its tormented past. Many who wander its towers at night speak of ghostly footsteps brushing against the stone floors, murmurs that rise and fall like the sigh of a restless spirit, and cries that vanish as suddenly as they appear. Some believe these are the voices of prisoners forever wandering, their anguish etched into the very corridors they once walked, never finding peace.

Yet not all tales of Yedikule are of suffering and despair. Long ago, during the Byzantine era, a magnificent seaside palace was said to shine where the fortress now stands. Adorned with gold and jewels so brilliant that the night itself seemed to glow, it contained a hidden crown room where an extraordinary jewelled crown was kept. Travellers' tales speak of its dazzling beauty, though time and exaggeration have blurred fact with legend. Still, this story of brilliance and mystery adds a different kind of magic to Yedikule, weaving wonder into the shadows of its haunted walls.

Yedikule in popular culture

Yedikule has long captured the imagination of artists and storytellers, becoming a distinctive backdrop in Turkish popular culture. In Turkish cinema, it frequently appears in films from the Yeşilçam era, a pivotal period in Turkish filmmaking spanning the 1950s to the 1980s. Named after a street in Istanbul where many studios were located, Yeşilçam became synonymous with prolific, low-budget productions that explored themes of family, love, struggle, and everyday life. Its melodramas, comedies, and socially conscious stories laid the foundation of the Turkish film industry, and directors continue to draw inspiration from the era’s unique storytelling style and emotional intensity.

The fortress and its surrounding city walls often appear in Yeşilçam films as atmospheric locations for tension, intrigue, or illicit activity. Narrow alleyways, shadowed towers, and imposing stone walls create a perfect stage for crime, smuggling, or clandestine meetings. Movies such as Baba Kartal (1978), Jilet Kazım (1971), Zavallılar (1974), and Yılan Soyu (1969) exploit the haunting and rugged scenery of Yedikule, using it to heighten suspense and underscore the gritty realities of life depicted on screen.

Beyond cinema, Yedikule's influence extends into literature. The fortress and its prison serve as the central setting in Ivo Andrić's novel "Prokleta avlija" ("The Cursed Courtyard"). Andrić, who won the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1961, immerses readers in the oppressive atmosphere of the prison, exploring themes of confinement, human suffering, and moral ambiguity. Almost the entirety of the novel unfolds within the walls of Yedikule, allowing the fortress to become not merely a location, but a character in its own right — a silent witness to the lives and struggles of those within.

Yedikule Gate

The Yedikule Gate, located between the 11th and 12th towers, just to the north of the Golden Gate, stood without flanking towers or stair-ramps. From the city side it presented a plain arched opening. On the landward side, its pointed double-brick arch, stepped buttresses, and cornices remain mostly intact, though the arch's keystone area is damaged. A second arch's buttress survives only in fragmentary form on the northern side.

The repair inscription on the arch belongs to Sultan Ahmed III (1703-1730), and tower 11 (to the south) was also restored under Ahmed III and Sultan Osman III. The Ottoman inscription (H. 1137 / 1724-25 CE) praises Sultan Ahmed III and extols his reign as one of justice and grandeur, describing him as the protector of religion and state, the builder of many works, and the originator of the gate's restored structure. The closing lines poetically compare the gate to a "symbol of the seven skies," linking its architecture to cosmic and imperial imagery.

The translation of the inscription is as follows: "The foundation of the reign of Sultan Ahmed Khan III, which shows all his glory and grandness, has been reinforced during his just reign. As he has been the shelter for the country and the nation, a sanctuary for the religion and the state, every part of our land has been protected from the traps of the enemy. Many other works were created during his reign; for example, the walls of Istanbul have been repaired and became the apple of the eye. Upon his order, Grand Vizier Ibrahim Pasha made sure it was repaired, and done so beautifully. Particularly, this dervish lodge became more splendid than all the others by the order of the Sultan, the ruler of the seven climates. Vehbi, Utarid, recorded the repair with these words: Yedikule Kapısı (The Gate of the Castle of the Seven Towers) now resembles the arch of seven heavens. 1137".

Some researchers interpret the gate's architectural features as Ottoman rather than Byzantine in style. The original front gate no longer exists, but a 19th-century illustration suggests it too had Ottoman character. Later archaeological work, aided by old photographs and drawings, proposes that the original front gate, now vanished, lay just south of tower 11, blocking the rear entrance.

Excavations and comparisons with historic illustrations show that this gate evolved over time. The original Byzantine front gate, long since removed, seems to have stood just south of Tower 11. It likely blocked the rear entrance to the fortress. A moat bridge, drawn farther south in old plans, once spanned the ditch before the walls.

A 1686 drawing shows the front and rear gates aligned, and the later Ottoman alterations appear to shift the entrance slightly northward. In the masonry of the curtain walls, one can still see a seam between two phases: a massive Byzantine wall on the south and a thinner Ottoman rebuild to its north. The Byzantine wall angles inward in an L-shape by about 30 cm — a feature also found in other gates, perhaps to allow door frames to sit flush.

Visitor tips:

After years of silence, Yedikule Fortress was carefully restored in 2020 and once again opened its gates to the public in 2021. By 2025, entry fees reflected a sharp divide: local residents could explore the storied towers for just 50 TL, while the tourists were asked to pay 250 TL. The fortress is closed on Mondays and on the other days of the week, it is open from 9:00 and 17:00.

The fortress is located within the Yedikule neighbourhood of the Fatih district of Istanbul. This neighbourhood is described in the article about the First Military Gate of the Theodosian Land Walls of Constantinople.

Getting there:

The most direct way to reach Yedikule Fortress is by taking the Marmaray line, the modern rail that runs beneath the Bosphorus and links the city's European and Asian shores. Step off at Kazlıçeşme Station and walk around 1 kilometre to the east. Within minutes, the ancient silhouette of the Seven Towers will rise before you. From the platform it is only a short walk, the path leading toward the monumental Theodosian Land Walls, whose stone bastions frame the fortress itself.

Another route begins with the M1a metro, which runs between Yenikapı and the old Atatürk Airport. Alighting at Topkapı–Ulubatlı, travellers can board a local bus or dolmuş bound for Yedikule. The ride is brief, weaving through the neighbourhoods that grew in the shadow of the Theodosian Walls, until at last the mighty towers of Yedikule appear above the city streets.

There is also the path for true history enthusiasts — a pilgrim's walk along the entire length of the Theodosian Walls. Beginning at the Golden Horn in the north, one can follow the massive fortifications as they march across the city to the shores of the Marmara Sea. It is a long trek, but one of the most rewarding in Istanbul: each section reveals a different face of the city, from bustling neighbourhoods to quiet stretches where ivy creeps across fallen stones. At the southern end of this journey, standing proudly at the walls' meeting point with the sea, the Seven Towers of Yedikule await — a fortress built on the bones of empires, and a monument that still commands the horizon.

Image gallery:

- Log in to post comments